Nintendo’s 16-bit catalog is stacked with heroic verbs, jump, blast, power-up, occasionally kart, but every so often a cartridge sneaks onto the shelf that replaces those verbs with a single, desperate imperative: run. Clock Tower (Super Famicom, September 14 1995) is that cartridge. It hands you a teenage orphan, a mansion dripping with gothic dread, and a pursuer whose hedge-trimmer shears flicker at ear-level like an ASMR nightmare. Is the game an unsung masterpiece or a clunky footnote? Both, perversely. It’s overlooked because localization never left Japan and because its point-and-click pacing looks arthritic next to the turbo doors of Resident Evil. Yet it’s indispensable because it hard-coded every stalk-and-chase loop modern horror depends on. Play it today and you realise how much mileage one SNES chip can squeeze from extended silence and a single, steel-on-tile scrape.

Historical Context

Human Entertainment had already cultivated a sceptical cult following by the mid-nineties. Their Fire Pro Wrestling series married granular grapple stats to sprite violence; their “sound novels” (Kamaitachi no Yoru, Majō Densetsu) used text and still images to raise gooseflesh on the Super CD-ROM². Against that backdrop, designer Hifumi Kouno pitched a side project: a playable slasher movie starring a heroine you couldn’t arm. Management approved a lean team and an eight-megabit memory budget, scant compared to the thirty-two-megabit bragging rights of Tales of Phantasia, and told them to deliver something new before 32-bit hardware left the SNES in dust.

Japanese pop culture was primed for grunge horror. Koji Suzuki’s Ring novel had kicked off a VHS-based fear cycle, Hollywood slashers were still showing up on import videotape, and PC gamers were talking about polygonal frights like Alone in the Dark. Nintendo’s console brand, meanwhile, was associated with Technicolor heroism. Dropping a silent, gore-tinted thriller onto the same shelf as Yoshi’s Island was audacity itself.

Western players didn’t get an official release. News arrived via import tips columns and ASCII-art bulletin boards: “You think Resident Evil is tense? Try a game where the killer spawns in any room and you have no weapon.” Such reports baited the bravado of would-be importers, myself included. One solder-smelling kiosk in Boston offered the cartridge for $89.99; the shop owner simply shrugged at my “Is it all Japanese text?” concern and said, “Kanji or not, you’ll figure out when to run.”

Mechanics

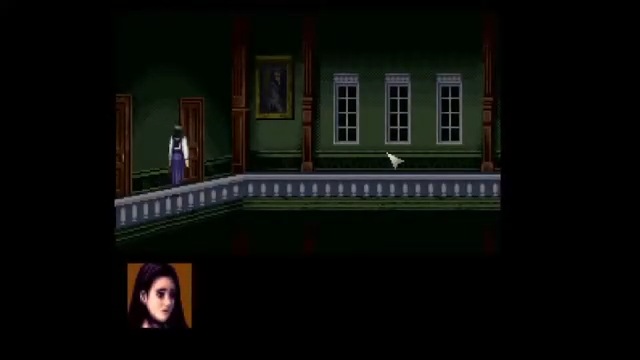

Jennifer Simpson moves through the Barrows mansion by way of a floating ghost-hand cursor. Tap A on a door, she walks. Double-tap, she jogs. Hold the button and she sprints in a panic that drains an unseen stamina value the developers never surface onscreen. You feel it only when her posture slumps, her portrait in the top left flashes crimson, and she begins tripping over nothing: visual feedback that arrives half a second before stainless steel tries to scissor your peripheral vision.

Rooms are stitched together by brief black-screen loads that last just long enough to spike your pulse. The mansion map rearranges at boot, items like car keys or ceremonial daggers may rest beneath the sofa one run and behind a birdcage the next. Scissorman’s appearances obey similar pseudo-random seed logic. Sometimes he crawls from a fireplace you inspected moments earlier, sometimes he smashes shower tiles while you’re debating whether to investigate a mirror. These uncertainties kill rote memorisation; you play not by pattern but by paranoia.

Defence is environmental, never personal. Jennifer can yank shelves onto Scissorman, kick buckets to stall him, or, most iconically, hide. Closets, dumbwaiters, even a meat locker become sanctuaries if you find them before fear paralyse clicks. Once inside, the game letterboxes, the score mutes, and a sub-bass heartbeat sample throbs. Footsteps scrape on floorboards outside. When the sound recedes you risk emerging; wait too long and the killer may still be there, timed to tear open your hiding spot for an instant frame that looked shockingly explicit on a console notorious for censoring sweat in Mortal Kombat.

Saving is automatic. Enter any new room and state data, inventory, corpse flags, puzzle shifts, writes straight to battery SRAM. There’s no mid-menu manual option, and you cannot cheese safety during pursuit; if Scissorman scalps you, the continue screen spits you back to your last doorway and you relive the dread with no guarantee the stalker will appear the same way twice.

Sound design outperforms its kilobyte footprint. Exploration unspools in near silence, punctuated only by grandfather-clock gears and Jennifer’s tap-shoes. The pursuit cue, a shrill two-note stinger riding distorted strings, hits like a panic button. Even more iconic is the mansion parrot. Veteran players swear hearing that voice clip in real life means their phone will buzz with bad news.

Interface jank becomes part of the challenge. The SNES D-pad drags the cursor with enough inertia that overshooting an exit under pressure is easy. Early fan-translation patches increased cursor speed and made the game tangibly easier, proving friction was a deliberate balance lever.

Legacy and Influence

Although Clock Tower never registered on Western sales charts, its design reverberated. When Human ported an expanded edition, retitled Clock Tower: The First Fear, to PlayStation and Windows in 1997, European magazines drew lines to both PC adventures and newly minted 3-D survival horror. Capcom later acquired Kouno’s blueprint for Clock Tower 3 and Haunting Ground, pushing the idea of a single antagonist AI unpredictably hunting the player. Step sideways and you can trace the lineage to Amnesia: The Dark Descent, Alien: Isolation, and countless “chase loop” indies. Designers constantly cite the SNES original for one principle: remove weapons, empower AI, profit in elevated heart rates.

Collectors keep the 1995 cartridge expensive. Low initial print runs, coupled with a 2000s fan-translation that spread interest faster than repro carts could keep up, mean boxed copies flirt with triple-digit auction prices. Data miners digging through the ROM uncovered unused Jennifer sprites brandishing garden shears, cut content that suggests a revenge ending where prey becomes predator. Whether memory constraints or tonal choice killed the asset, the find nourishes what-ifs among modders.

Speedrunning communities treat the randomisation as both devil and deity. Current S-ending any-percent record hovers around twelve minutes on original hardware, a feat requiring favorable item seeds and fearless manipulation of Scissorman’s spawn cooldowns. Watching a champion runner hide, step out two seconds early, then slide behind a door he knows will load-warp the killer into oblivion is to witness glitch theory masquerading as slasher choreography.

Closing Paragraph + Score

Turn on Clock Tower in 2025 and its pixels look quaint, but the menace feels fresh. You’re not counting bullets or solving complex inventories; you’re breathing with a sprite whose every stagger telegraphs that another stumble equals shears against bone. The absence of a visible stamina meter makes the panic visceral; the inability to spam a save menu keeps every experiment costly. If fear is anticipation multiplied by helplessness, Human Entertainment solved the equation three decades back and wrote it onto 8-megabit silicon.

Score: 8.5 / 10. Path-finding hiccups and slow cursor drift occasionally fracture immersion, but those blemishes feed the dread machine more than they break it. Silence, random stalker logic, and a parrot that shrieks homicidal intent together deliver set-piece tension bigger budget horror still chases. In a library packed with cheery platformers, Clock Tower reminds you the Super Nintendo could do darkness, and do it well enough that you’ll hesitate before opening the next closet in real life.