Every medium-sized generation gets its rite-of-passage fantasy kid. The ’80s crowned Atreyu on a luck-dragon, the 2000s produced Harry under a staircase, and wedged neatly between them lurks a ginger teenager in a robe two sizes too big whose most devastating spell is weaponised sarcasm. That, fellow retro spelunkers, is Simon, reluctant hero of Adventure Soft’s 1993 DOS adventure Simon the Sorcerer. Bizarre or classic? Both, in a Monty-Python-meets-Monkey-Island sort of way. Underrated? It charted above Sam & Max for several weeks on Britain’s Amiga Top 10, yet Americans barely noticed. Overrated? Only to LucasArts purists who insist puzzle design reached its zenith at Stan’s Used Coffin Shop. Fundamental? Absolutely: it proved voice-led comedy didn’t have to sail from Marin County, Staffordshire could sling punch-lines just as slick. Negligible? Only if you can ignore a game that makes “teenage snark” an executable mechanic. (Rhetorical question: can a floppy disk deliver British irony by the megabyte? Self-answer: oh, yes, and it does so with a grin wider than a Discworld turtle.)

Historical Context

By late 1992 Britain’s adventure scene was a boutique affair. Revolution’s Lure of the Temptress flirted with AI innovation, and Horror Soft’s Elvira mixed parser RPG with B-movie cheesecake. Mike Woodroffe, veteran of both outfits, re-emerged as Adventure Soft and set his sights on LucasArts’ comedy crown. He drafted his teenage son, Simon Woodroffe, as designer, reused the proprietary AGOS engine, and promised retailers a fantasy romp “as funny as Monkey Island and unmistakably British.”

Eleven DOS floppies, with audio compressed to ADL, hit U.K. shelves on 2 December 1993, while a nine-disk Amiga version followed days later. A North-American DOS release shipped through GT Interactive in spring 1994 with minimal fanfare. Two years on, the studio pressed a CD-ROM “talkie” edition voiced almost entirely by Red Dwarf alumnus Chris Barrie, who, legend says, recorded every line during a 40-hour tea-fuelled marathon. A single Red-book track by superstar Richard Joseph adorns the intro, but the in-game score is the handiwork of Paul Mokhtarzada with producer Mike Woodroffe, their MIDI cues ducking around Barrie’s rapid-fire delivery.

The talkie disc landed smack between LucasArts’ Full Throttle hype cycle and Sierra’s Phantasmagoria FMV parade. British magazines hailed it “a home-grown national treasure,” while PC Gamer UK nudged readers to upgrade from floppy if they wanted Barrie’s line, “Wizards? Don’t they play third base for the Mets?” delivered with proper exasperation.

My own initiation happened on an XP Arcade 386 that lacked a sound card; Simon’s voiceless eyebrow arches still killed. When a talkie copy arrived, the clerk deemed it “the one adventure that made teenage sarcasm aspirational.” Even then, the floppy run kept selling: chart reports put Simon ahead of Day of the Tentacle on the Amiga Top 10 during January 1994, a feat that might say more about British hardware penetration than global sales but still raises eyebrows.

Mechanics

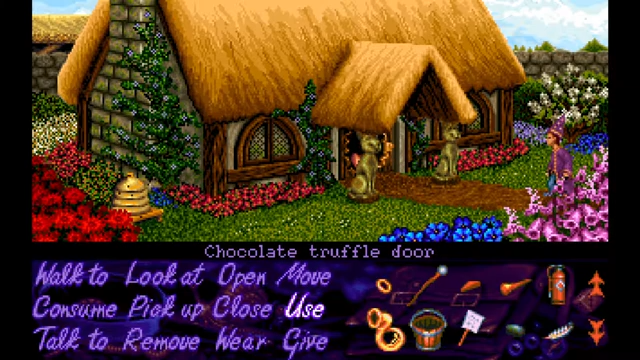

The Six-Verb Bar and Infinite Snark

Once the magic wardrobe spits Simon and his terrier into Calypso’s cottage, the AGOS interface appears: WALK, LOOK AT, PICK UP, USE/GIVE, TALK TO, and OPTIONS, no separate “sarcasm” button, because sarcasm is Simon’s default tone whenever you click TALK TO. Selecting his mouth cursor on a cauldron elicits, “Ugh, caldo-espresso for trolls?” Try to PICK UP a sleeping dwarf and he retorts, “I prefer my teddy bears less bearded.” These context gags replace Sierra’s instant-death tradition with ego bruises; the floppy edition ships with 3,000 lines, the CD almost 6,000.

Puzzle Constellations

Adventure Soft glued Lucas-style inventory chains onto an open hub of fairy-tale biomes. Early progress hinges on brewing Swamp Stew so a woodcutter ogre clears your path. Ingredients involve enticing leeches off a frog (using salt stolen from a pub quiz), barbecuing a rat for garnish, and siphoning swamp water while a hovering woodworm heckles you. Every solution is mad but internally logical, unlike Sierra’s cat/mustache fiascoes. The mid-game leans into Monty-Python farce: you must trick a druid conference into believing Stonehenge has moved; later you browbeat Tolkien dwarves about union rates to borrow their beard comb. ACOS’s fast-travel “Magic Map” spares you the backtracking malaise that haunted many VGA contemporaries.

Quality-of-Life & Fail States

Simon can “sprint” via double-click exits and will autowalk around minor obstructions, an engine tweak Adventure Soft introduced after play-testers ranted about Elvira’s plodding pace. Deaths are rare; the worst punishment is circular sarcasm if you try USE LADDER with SUNBEAMS. The only semi-soft-lock is failing to pick parsley before a dragon incinerates it, designers inserted a second parsley spawn in patch v1.1 to be safe.

Aesthetic & Audio

Backgrounds, scanned from pencil sketches and meticulously coloured in Deluxe Paint, still pop in DOSBox. Dappled forest light, roiling swamp bubbles, and the wizard tower’s Escher stairs: all show British cartoon lineage. Paul Mokhtarzada’s score waltzes between jaunty recorders and ominous organ lines; each area’s leitmotif loops under 30 seconds to fit disk space yet avoids annoyance, no small feat. The CD speech balances across Red-book channels, no compression, so Barrie’s asides sometimes drown music, purists toggle subtitles to savour each pun.

Legacy and Influence

Critical reception glowed: PC Zone 92 %, Amiga Action 90 %, Computer Gaming World in the U.S. dropped to 3½/5, praising humour but wagging a finger at “too British references.” Sales numbers remain vague; designer Woodroffe only claimed “a solid six-figure total” when asked by Retro Gamer in 2013. Chart data, however, shows the floppy sitting atop UK Amiga listings for five weeks, edging above Day of the Tentacle.

Cultural impact quietly snowballed. Charles Cecil later cited Simon when defending full voice casts for Broken Sword. Dan Connors noted its dense pop-culture tapestry while shaping Sam & Max episodic scripts. Fan translators ported Simon into Polish, Czech, and Spanish talkies, some using community dubbing funded on Kickstarter. ScummVM’s 2004 support resurrected floppy editions on smartphones, leading to iOS and Android ports in 2009 by MojoTouch.

Sequels? Simon 2 refined art and introduced that famously opinionated talking hat, but 2002’s Simon 3D stumbled with stiff polygons. After IP shuffles, small-team follow-ups emerged (Chaos Happens, Who’d Even Want Contact?!) yet none eclipsed the lightning-in-a-diskette humour of the first.

Why not a household name stateside? Marketing budgets were microscopic compared to LucasArts; many jokes hinge on BBC tropes; and floppy installs in ’94 still required memmaker gymnastics. Yet ask any European point-and-click veteran and Simon ranks shoulder-to-shoulder with Guybrush, ginger fringe, baggy robe, and a quip for every fourth wall.

Closing Paragraph + Score

Booting Simon the Sorcerer in 2025 is like cracking a forgotten Terry Pratchett paperback: dog-eared yet dazzling, jokes twinkling with adolescent mischief and surprisingly sharp craft. Its puzzles tease but seldom troll, its colours burn brighter than VGA has any right to, and Chris Barrie’s performance remains a comedic clinic. Minor grievances, occasional pixel hunt, Brit-centric references that sail over non-UK heads, barely dent the grin factor. Twenty-plus years on, Simon proves that the real magic lies not in wands or wardrobes, but in a teenager’s inexhaustible supply of snark.

Final verdict: 9.0 / 10. It’s not just a relic; it’s a living spell, one that turns point-and-click into point-and-snicker and reminds us that saving the realm goes down easier with a side order of sarcasm.