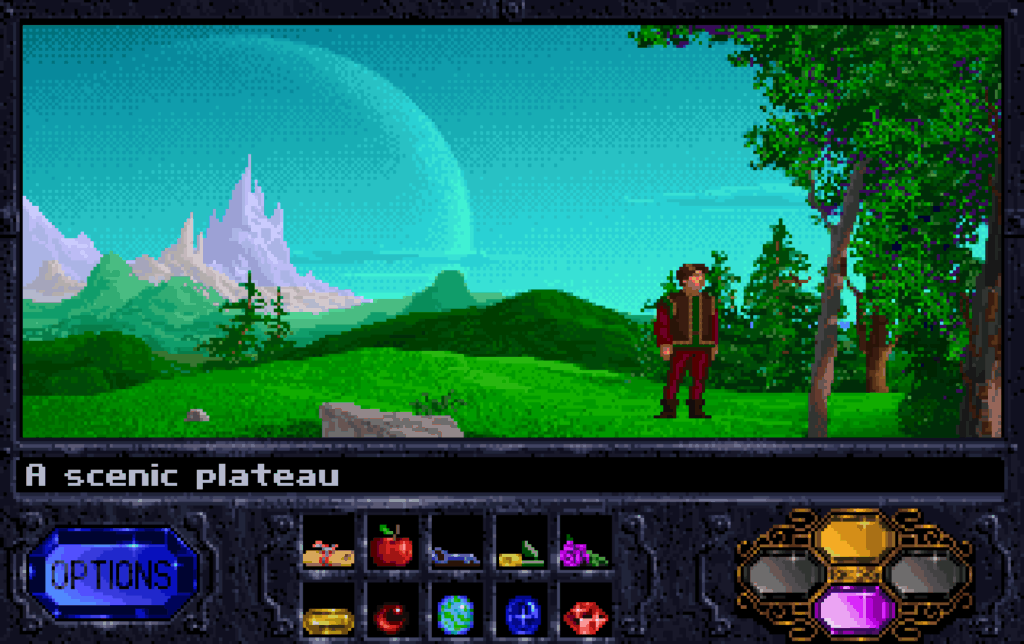

We already know early-’90s adventure games either delighted in murdering you for mis-clicks (hi, Sierra), drenched everything in self-aware snark (hello, LucasArts), or protected their secrets with novellas of lore that doubled as copy-protection (looking at you, Ultima VII). But what about a title that looked like Disney concept art, sounded like an Amiga demo-scene mixtape, and lectured you on botanical fire-safety with a completely straight face? Welcome to Westwood Studios’ The Legend of Kyrandia. Bizarre cult classic or undervalued cornerstone? Yes. Simultaneously. It’s the game that hands you nine inventory slots, fills them with more glowing gems than a Bejeweled high score, and then cackles as you juggle fireberries that expire faster than milk in a heat wave. Hyperbole? Always. Irony? Inevitably. Rhetorical questions trailed by self-deprecating answers? Could I possibly unpack this pixel fairy tale without them? Spoiler: not a chance. Strap on your best emerald-smeared mouse hand, gather those flame-berries, and follow me into a realm where a murder-clown jester narrates your pain and an enchanted amulet doubles as the universe’s most chaotic Uber.

Historical Context

By mid-1992, Westwood Studios was best known for Eye of the Beholder II and the tactical pedigree that would soon become real-time strategy gospel. Publisher Virgin Games, flush with Dune II anticipation money, wanted something friendlier to younger PC owners, Sierra levels of accessibility, LucasArts levels of charm, but with Westwood’s painterly artistry. The internal codename “Fables & Fiends” survived half of development until marketing feared it sounded like sugared cereal. The Legend of Kyrandia shipped in August 1992 on both DOS and Amiga, seven high-density disks in the States, eight in Europe thanks to localized voice stingers.

Co-founder Brett Sperry steered production; designer Michael Legg mapped puzzle logic; lead artist Rick Parks coated backgrounds in parallax forests and phosphorescent caves; and composer Frank Klepacki (with additional cues from Dan Kehler, plus supervisory polish by Chris Braymen and Mark Seibert) scored the woodwind-heavy soundtrack that hid PC-speaker squeals beneath AdLib velvet.

Virgin bundled a lush manual and a glossy quick-reference card in case you forgot that right-click cycles the cursor. Sales landed near 250 000 units in the first year, respectable if not seismic, enough to green-light sequels Hand of Fate (1993) and Malcolm’s Revenge (1994). Critics drooled over the VGA palette, called the music “storybook Spielberg,” and declared Westwood the studio to watch just months before the company detonated the RTS genre with Dune II.

I met Kyrandia via a Babbage’s kiosk on a ludicrously overpriced 486. The store bag’s metallic-green ink rubbed off on my sweaty teenager palms, a stain that became my personal absurd motif whenever the game forced me to carry yet another emerald gem. That stain returns throughout this article, usually after a fit of inventory rage.

Mechanics

Single-Cursor Sanity, and Insanity

Westwood flogged the death-free pledge: no unwinnable states, fewer cheap fatalities. Technically true, yet the design weaponizes inconvenience. The evergreen bottom-center inventory grid offers exactly nine slots, no scrolling, yet the critical path demands you wrangle at least a dozen unique items: elemental gems, fireberries, keys, fruit, and the all-important flask of enchanted dew. Decide what to drop and where; teleport flowers can retrieve lost loot, but only if you remember which bloom warps where. It’s artisanal back-tracking, served cold.

Fireberry Management: Kyrandia’s Unofficial Day-Night Cycle

Chapter Two is a master class in soft pressure. Brandon’s lantern must burn fireberries through pitch-black woods. In the DOS build the berries dim after about eight screen transitions (the Amiga release trims that to roughly five), at which point your lantern sputters and a death shriek cues Brandon’s skeleton overlay. Each expired berry triggers frantic back-tracking to the glowing bush, intensifying inventory anxiety: carry fewer trinkets or risk another skeleton cut-scene. Sierra would’ve called it “a learning experience”; LucasArts would have cracked a joke. Westwood simply smirks, letting the tension stew.

Puzzle Logic: Fair, with Occasional Madness

Westwood’s pledge of “no death traps, no dead ends” means you’ll never hard-lock, but you can strand yourself in comedic limbo if you drop a vital gem on the wrong continent. Solutions are whimsical yet internally consistent: water a stunted tree with magic dew to sprout the beanstalk; soothe a grumpy dragon with a flute melody learned from a signpost. The controversial outlier is the ice-cave bridge: solving it requires a prophecy that references fruit colors you saw three screens earlier. Mis-order the gems, and Brandon plummets. Cue that green bag slap as I spill peach Snapple on graph paper labelled “CERISE ≠ CRANBERRY???”

Thankfully, Brandon’s magic amulet adds ergonomic relief: it grows new powers after each chapter, translation runes, teleport glitch, “ooh shiny” gem locator chirps. By late game the amulet hums like a Swiss Army knife, transforming fetch-quest tedium into giddy warp-scumming. It’s the adventure equivalent of Metroid’s screw attack, once unlocked you’ll mash it purely for dopamine.

Character & Tone: Brandon the Blank Slate, Malcolm the Murder Clown

Players still argue whether Brandon is charmingly understated or a bran-flake of a protagonist. He mostly quips “Gee, wonder what this does?” then moonwalks to the screen edge. The real personality flows from NPCs: Darm, whose self-inflicted spells turn him from old wizard to basset hound; Zanthia, the sardonic alchemist previewing her sequel stardom; and Malcolm, that sapphire-eyed jester who pops into picture-in-picture taunt mode whenever you succeed or fail. His cackles prefigure Handsome Jack by twenty years, if Handsome Jack wielded lawn gnomes instead of Hyperion bots.

Legacy and Influence

Kyrandia never achieved LucasArts ubiquity, yet its DNA spread quietly. The one-cursor interface inspired later indies like Thimbleweed Park to streamline verb fatigue. The fireberry-lantern tension resurfaced spiritually in Don’t Starve’s sanity-draining darkness. And Westwood’s approach to environment-centric humor, letting trees complain when you pick their fruit, showed up in Daedalic’s Deponia trilogy.

Design lineage, not literal code, trickled into Westwood’s RTS path-finding: team members have said that building Kyrandia’s walk-mesh system primed their thinking for unit movement the next year on Dune II. Consider Brandon’s stiff sprint the ancestor of every “moving out!” infantry clip in Command & Conquer.

Speed-runners adore Kyrandia for the dev-left debugger: Hold both Shift keys and tap F7 to fast-forward dialogue. Combined with teleport-flower routing, the any-percent record hovers around 27 minutes, staggering for a game that took me weeks the first time. The bag stain returns here: speed-runners call rapid item-drop optimization “green-bagging” (a term I wish were canon).

Closing Paragraph + Score

So what is The Legend of Kyrandia in 2025? It’s the emerald-ink palmprint haunting adventure gaming’s collective memory, visible only when you tilt nostalgia against the light. It’s nine inventory slots daring you to hoard color-coded MacGuffins. It’s a torch that burns out just shy of safety, a wizard who becomes a dog for the pun of it, and a jester whose laugh still loops in my Sound Blaster nightmares. Less witty than Guybrush, less vindictive than Graham, yet so visually lush and mechanically tight that its shortcomings morph into charm.

Final verdict: 7.5 / 10. Add two points if parallax forests and Amiga-lush audio outweigh mild moon-logic; subtract one if inventory claustrophobia gives you hives. Either way, keep an eye on those fireberries, store the gems in chromatic order, and remember, next time Malcolm cackles, slap that imaginary green bag and grin right back.