Is Infogrames’ 1993 cosmic creeper Call of Cthulhu: Shadow of the Comet an unsung classic or a creaky footnote, a crowning jewel of VGA horror or a half-remembered fever dream you accidentally installed from a cover‑disk while looking for shareware pinball? (Answer: all of the above, plus a side order of tentacles.) In an industry year dominated by shiny CD-ROM roller‑coasters like The 7th Guest and the testosterone tsunami of Doom, here came a third‑person, keyboard‑only, flip‑screen adventure that asked you to map out a sleepy New England fishing village, photograph Halley’s Comet, and maybe, just maybe, avoid being eaten by an elder god the size of Rhode Island. Bizarre or classical? Yes. Underrated or overrated? More people have heard of Yog‑Sothoth than of protagonist John T. Parker, so let’s file it under criminally neglected. Fundamental or disposable? Considering how many later horror games lifted its real‑time schedule, time‑gated puzzles, and catatonia‑inducing jump‑scares, I’d say it’s an essential ancestral strain (one preserved in formaldehyde next to a jar labelled “Phantasmagoria’s acting choices”). And in case you’re wondering whether it still plays in 2025, I have two rhetorical questions: do nightmares age, and why does my DOSBox folder now smell faintly of dead fish? Self‑answer: nightmares never age, and that’s not your hard drive, Illsmouth’s docks are leaking through the screen again.

Historical Context

Let’s crank the calendar backward to spring 1993. Infogrames, still pronounced “INFRO‑grems” by 50 percent of American gamers, was riding a weirdly eclectic wave: cartoony platformers like Alone in the Dark’s kiddie cousin Alone in the Dark: Jack in the Dark; regional oddities starring armadillos in berets; and, crucially, H. P. Lovecraft adaptations that let the French studio indulge its inner goth. Alone in the Dark had already detonated the 3D survival‑horror toolbox the previous year, so for a follow‑up they swerved back to two dimensions, convinced that a more traditional point‑and‑click (minus the click) could deliver pure, undiluted dread. This was the era when publishers still believed bigger manuals equaled prestige, Shadow of the Comet shipped with a novella‑length journal, sepia newspaper clippings, and copy‑protection riddles about long‑dead astronomers, the sort of papier‑mâché meta‑lore Kickstarter collectors drool over today.

The game also slid neatly into a broader pop‑culture trend: 1993’s mainstream rediscovery of cosmic horror. Chaosium’s tabletop RPG Call of Cthulhu was celebrating a dozen years of sanity‑shattering dice rolls; Metallica had howled Lovecraft’s name over stadium speakers; and Alan Moore was busy folding eldritch gods into Swamp Thing trade paperbacks. Yet the PC space was largely content with chainsaw demons and FMV serial killers. Infogrames saw a gap wide enough for an interdimensional squid and pounced.

I first met Shadow of the Comet in a dingy electronics aisle sandwiched between WordPerfect5.1 and bargain‑bin Mystery of the Druids. The box art, a lone astronomer framed by a chalk‑white comet tail above salt‑bleached clapboard houses, looked like Norman Rockwell Goes to R’lyeh. I slapped down lawn‑mowing money, lugged home five 3.5‑inch high‑density floppies (the common DOS release; the 5¼‑inch version infamously needed seven), and promptly spent an hour deciphering the French installer’s default path (C:\JEUX\COMET, naturellement). Launching the EXE, I was greeted by a MIDI overture equal parts Debussy and doom metal, and a title card that declined any mention of Alone in the Dark as if to say, “Different beast, same nightmares.”

In hindsight the timing was uncanny. Doom would drop in December and redraw the map of interactive horror around twitch reflexes, but for one fleeting pre‑id moment, Infogrames’ New England nightmare was the scariest ticket in town, drenching VGA palettes in fog and existential dread rather than arterial spray. When critics called it “old‑fashioned,” Infogrames countered with a Gallic shrug: sometimes the oldest methods, slow burns, literary obsession, dialogue thick with archaic dread, leave the deepest scars. (Also, the studio’s 2D toolset was cheaper than polygon R&D. Budgetary tentacles, meet cosmic tentacles.)

Mechanics

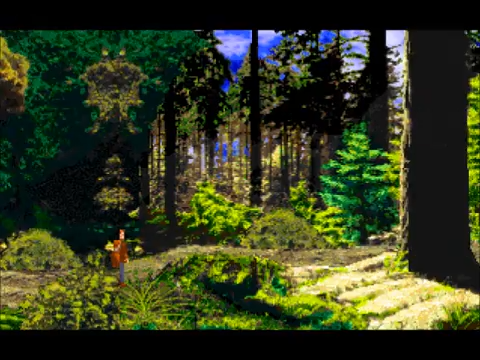

Imagine if Maniac Mansion ditched its mouse cursor, borrowed Prince of Persia’s rotoscoped fluidity, then forced you to memorize an entire town’s timetable like a Victorian train conductor hopped up on laudanum. That’s Shadow of the Comet in a phial of ichor. You steer JohnT.Parker, note the T; I like to pretend it stands for “Temporary Sanity”, with the arrow keys. There is no universally‑beloved mouse support; critics at the time compared the keyboard pathfinding to parallel parking a ModelT under strobe lights. Objects sparkle only if Parker’s line of sight intersects them (a thin white beam snaps from his pupils to the hotspot), a clever diegetic flourish that doubles as pre‑Photoshop lens flare.

The game structure unfolds over three in‑game days, loosely sliced into morning, afternoon, evening, and nightmare‑fuel night. Events trigger whether or not you show up, meaning you can miss plot beats and soft‑lock yourself into cosmic oblivion faster than you can say “Necronomicon paperback edition.” On day one you might bump into town spinster MissPicott, who offers a cryptic “bless your heart” (translation: horrified pity) while hinting at subterranean tunnels; fail to follow up before dusk, and by sunrise she’s catatonic, your clue lost to mania. It’s the narrative equivalent of juggling chainsaws lubricated with fish oil: deliciously stressful.

Puzzles swing between grounded (mix developer fluid in the darkroom so your comet photos don’t bleach out) and “did I inhale paint thinner?” (steal a ceremonial dagger guarded by chicken‑wire barns, then swap it with a fake forged from melted church bells). My personal white‑hair moment involves the town library’s locked reading room. The key sits inches from Parker’s fingers, but a librarian blocks you like Gandalf in tweed. The solution: distract him by tearing a specific page from a newspaper archive located in another building, bring it to him under the guise of “rare document preservation,” wait until he wheels out a humidity meter, then grab the key while chanting “this is fine” louder than Parker’s internal monologue.

Set pieces punctuate the point‑and‑prowl routine with proto‑survival‑horror tension. A midnight graveyard chase sees robed cultists skitter through snow like glitched Pac‑Man ghosts; one wrong turn, and Parker meets a pickaxe to the sternum, cueing the infamous game‑over voice‑over, an Alan Bennett‑esque actor intoning, “Poor Parker, so young and already in the next world,” a line you will learn to hate‑love as deaths mount into the double digits. Later, Parker spelunks beneath Illsmouth’s lighthouse, descending ladders that creak in CGA‑memories of King’s Quest, only for the screen to bloom red as Dagon’s spawn surge in Mode13h pixel fire. Every death rewinds the clock but not your pulse: DOS horror understood psychological attrition decades before roguelikes made it fashionable.

Graphics deserve their own sanity check. Infogrames rotoscoped faces from vintage Hollywood stills, TVTropes sleuths have spotted Robert Mitchum, Sydney Greenstreet, even a side‑eyeing Jimmy Stewart cameo, slapping them onto 320×200 bodies like eldritch Mr. Potato Heads. The effect is uncanny in the literal Freudian sense: simultaneously realistic and papier‑maché, as if you’re watching an after‑hours séance where Golden Age actors read stage directions from Weird Tales. The absurd element I promised earlier? Parker’s camera tripod. It floats in and out of reality, sometimes visible as a full sprite, sometimes implied by a single clicking shutter sound, like Schrödinger’s selfie stick. I spent half the game convinced the tripod was the true avatar of Nyarlathotep, manipulating inventory slots when no one was looking. (Could I prove it? No. Did it spook me more than any fish‑man jump‑scare? Absolutely.)

Sound design marries early‑’90s MIDI with staccato digitized effects: wooden doors groan like bassoon solos; waves hiss in white‑noise bursts; cult chants drone in crunchy 8‑bit reverb. Play through Sound Blaster speakers and it feels charmingly archaic; slap on modern headphones and the low‑fi grit mutates into ASMR from the abyss. The score main‑themes a waltz that modulates into tritones whenever you examine anything involving tentacles, subtle as a shotgun wedding, but effective.

And yes, the game is punishing. Save‑anywhere softens the blow, but nothing prepares you for “gotcha” logic leaps: fail to photograph the comet from the exact pixel on the roof before 2:03a.m., and Parker loses a sanity point you never knew existed, chaining into death by dawn; answer a policeman’s question with slightly wrong phrasing, land in the county jail, watch the inevitable cut‑scene of Shoggoths liquefying the cell bars. Still, each brutal checkpoint feeds the story’s core thesis: cosmic forces don’t care about your user experience. Be thankful the Old Ones grant you F5 quick‑save privileges at all.

Pop‑culture parallels stack high. The real‑time day cycle foreshadows Majora’s Mask by seven years, the death‑loop puzzle‑solving anticipates Outer Wilds by a full quarter‑century, and the oppressive small‑town paranoia clearly drinks from the same brackish well as Twin Peaks (1990) and In the Mouth of Madness (1994). Meanwhile, inventory micro‑agony, combine X with Y at Z o’clock or else, mirrors Gabriel Knight’s hotspot hunts but slathered in barnacle slime. I cannot overstate how gleefully unmerciful it is; completing Shadow of the Comet without a guide remains a badge of honor akin to beating Battletoads co‑op without therapy.

Legacy and Influence

So why isn’t Shadow of the Comet name-checked in every “Horror Game Hall of Fame” tweetstorm? Blame timing, marketing, and a dash of Gallic contrarianism. Infogrames re-issued it in ’96 with the Chaosium-approved prefix “Call of Cthulhu,” but by then adventure sales were drowning under FPS tsunamis and LucasArts’ slick SCUMM finales. Reviewers admired its story yet sneered at keyboard controls (Computer Gaming World called manipulating objects “painful”, and they were grading on a Ultima VIII curve). The big boxes vanished from retail faster than Parker’s sanity, and the CD-ROM generation forgot Illsmouth existed until GOG resuscitated it alongside sequel-in-spirit Prisoner of Ice in 2015.

Influence, however, lingers in design DNA. Ask Frictional Games’ founders about their pre-Amnesia inspirations, they’ll mention the vulnerability, the locked-door dread, the literary aesthetic. The fixed-event schedule crops up in Deadly Premonition, Pathologic, and The Sexy Brutale. The idea that death messages could be narratively voiced (and darkly comedic) blossoms in Resident Evil’s “You Died” stingers and Dark Souls’ infamous crimson typography. Even modern Call of Cthulhu titles, from Cyanide’s 2018 RPG to indie visual novel mash-ups, borrow elements: coastal decay, journalist protagonist, comet-related occultism. Yet none replicate that stag-night mixture of methodical exploration and spiteful booby traps.

I’d argue its real gift is tone. Where later Lovecraftian games lean fully into tentacular boss fights, Comet savors the slow suffocation of curiosity: you want the perfect comet shot? Fine, here’s the key, the lens, the secret lighthouse ladder, hope the ritual circle doesn’t object to your tripod. That academic arrogance fueling Parker (and, by proxy, the player) bleeds into countless indie horrors that punish out-of-depth scholars: think Anatomy’s cassette-tape psychoanalysis or Signalis’ archives of doomed research.

Yet the game remains niche because its pain points are foundational, not patchable. The walk-until-sprite-aligns controls feel prehistoric next to even mid-’90s SCUMM. The opaque fail states make Sierra classics look forgiving. And its reliance on Lovecraft deep-cuts, quotes from The Shadow over Innsmouth plastered on grave markers, can alienate casual occult tourists. In other words, it’s a cult game about a cult, self-selecting its congregation. But oh, to be part of that doomed congregation, trading hand-drawn maps on Usenet, arguing whether the librarian is secretly modeled on Peter Cushing or Christopher Lee. (Answer: both, spliced in a gene-splicer powered by typewriter ribbon.)

Closing Paragraph + Score

Booting Shadow of the Comet today feels like slipping into a creased oilskin journal, its margins scrawled with equations about comet trajectories and doodles of fish-eyed villagers. Every keyboard nudge resurrects 640 kB ghosts: the creak of Illsmouth’s wharf, the librarian’s frown, the hiss of Parker’s camera shutter, the tripod still hovering, still mocking. Is the game perfect? Of course not; it throws user-interface tantrums, commits difficulty war crimes, and sometimes strands you in pixel-hunt purgatory because the designer loved lunar eclipses more than sign-posting. But perfection is the enemy of dread. Shadow of the Comet is messy, merciless, magnificently weird, an arthouse horror film projected through a VGA kaleidoscope, daring you to document the cosmos and survive the exposure. My final self-inflicted verdict, etched in astral runes and smudged with darkroom chemicals: 8.6 / 10. Docked a full point for making me replay an entire day because I forgot to pick up a length of rope, shaved another four-tenths for not letting the tripod be the secret final boss, and awarded the rest for reminding me that sometimes true horror is fumbling for arrow keys while a comet blazes overhead, illuminating how small we really are.