Is Blue Force the DOS adventure equivalent of an over-caffeinated ride-along, half procedural sermon, half off-brand action flick, lying forgotten in the glove compartment of history? (Rhetorical question. Self-answer: obviously, yes.) Jim Walls, the ex-highway patrolman who gift-wrapped Police Quest for Sierra, split from Oakhurst in ’92, joined Tsunami Media, and immediately decided that gamers everywhere deserved a spiritual successor that shouted “FOLLOW THE RULES!” louder than a DMV audio-loop. The result landed in 1993: a VGA cop thriller that mixes methodical evidence-bagging with day-time soap vengeance, then sells an add-on service that let real players mail in a videotape so their pixel head could cameo at City Hall for a measly $29.95 (peak ‘90s, right?). Underrated? Completely. Over-hyped? How can a game be over-hyped when half the hobby still spells its title Blue Force as two words and assumes it’s a Sega beat-’em-up? It’s neither cornerstone nor curiosity cabinet trinket, it’s the intermediate evolutionary fossil connecting Sierra’s point-and-click era to the full-FMV wave that would swamp CD-ROM bins within a year. And if that sounds grandiose, trust me: no other adventure ever greets you with a police motorcycle, a ticket book, and an in-universe coupon promising to inject your likeness into its VGA canvas. That coupon is my absurd red thread, and I plan to tug it until somebody issues me a citation.

Historical Context

Tsunami Media, founded by Sierra refugees in the eastern Sierra foothills, aimed to surf the crest of the interactive-movie boom without drowning in licensing costs. They published Ringworld: Revenge of the Patriarch for sci-fi lit nerds, Silent Steel for FMV sub-sim junkies, and a Ken Allen soundtrack anthology for audio-chip romantics. Into this eclectic portfolio slid Blue Force, built with TsAGE, essentially a refurnished SCI engine painted beige so Sierra legal couldn’t sniff it out. Walls brought along background artist Jerry Moore and, crucially, composer Ken Allen, whose brass stabs had previously sold Sonny Bonds’s heroics in Police Quest III.

By 1993, adventure design was mutating. LucasArts had abandoned parsers for icon bars, while Sierra’s Gabriel Knight pushed talking portraits and CD speech. Tsunami, lacking the capital for full voice-over or home-video actors, doubled down on a single promise: Blue Force would model real police work down to the last Miranda phrase. The game shipped on three 3.5-inch disks (five if you wanted the extra VGA portrait pack) and arrived in stores beside Day of the Tentacle and Return to Zork. In an era obsessed with blast processing and FMV star power, Walls bet that strict procedural authenticity, and a pay-to-cameo gimmick, could keep the badge shiny.

That gimmick still boggles me. Tsunami’s box insert, headlined “Get Injected!”, invited players to record 10 seconds of themselves slowly turning left, then right, against a white wall. Mail the tape, along with twenty-nine bucks plus postage, and Tsunami promised to digitize your face into a non-interactive crowd shot at Clarksbury City Hall. They would then return a personalized floppy disk patch so you could boot your cameo on any 486 in the neighborhood. It was cameo culture before Tony Hawk created custom skaters, before WWE games let you scan selfies, before social media filters existed. It is also, in retrospect, one of the craziest marketing swings of the DOS era because it required: (a) a camcorder, (b) parents who wouldn’t tape “Days of Our Lives” over your submission, and (c) faith that a small California studio wouldn’t vanish before mailing the disk back. I never scraped together the cash, my summer job money went to Sound Blaster upgrades, but the very idea seared itself into my teenage neurons, where it remains, pulsing like a neon OPEN sign.

Mechanics

Badge Before Bluster

You step into the sensible shoes of rookie officer Jake Ryan, a patrol cop with raw nerves and a decades-old vendetta. The interface sports five icons, walk, look, talk, hand, and badge, arrayed around a blue ribbon UI. There’s no explicit “notebook” button; instead, invisible event flags track whether you’ve followed protocol. Skip a step and the game either deducts points or slaps you with an immediate Game Over reminiscent of a captain yanking your gun and badge. I once forgot to radio in a license plate before approaching a speeder, and the screen cut to a text reprimand so smug it could have been printed on a parking ticket: “OFFICER RYAN, PROCEDURE IS NOT A SUGGESTION.” Reload city.

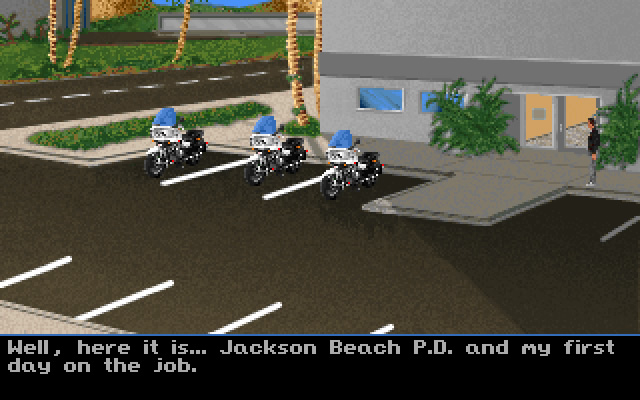

Morning Shift: Motorcycle Patrol

The opening act throws Jake onto a police bike cruising the coastal highway near Clarksbury, a lightly re-skinned Santa Cruz. It’s a side-scroll segment where you accelerate with the arrow keys and tap Ctrl for the blinker. Ignore the blinker and dispatch squawks; blow a stop sign and a dramatic crash animation barrels in from stage right, totaling the bike, ending the shift, and punting you back to the main menu. This is Road Rash with no punching, just paperwork-rage. Pulling over a violator launches a conversation screen: you must greet, identify, request license, and wait for the license to change hands before clicking the radio icon. Jump the order? You’re docked points. Forget to return documents? Same punishment. The game’s friction becomes its texture; every mundane chore is a rivet you can hear squeaking.

Crime-Scene Rigor Mortis

Walls’s fetish for evidence handling puts classic adventure object puzzles to shame. At a liquor-store robbery, you must photograph shell casings, bag them, then label each bag with the preprinted property tag sitting two screens away in the cruiser trunk. Photographing happens through a camera cursor that overlays crosshairs; bagging swaps to an inventory sub-screen where you drag the casing icon onto a plastic pouch. Miss the label and the chain-of-custody flag fails silently until the district attorney tosses the evidence during a post-mission wrap-up. Nothing bleeds player morale faster than realizing hour-three mistakes invalidate hour-six victories.

Hospital Interlude

Midway through his investigation, Jake’s patrol bike gets sideswiped by a black van tied to gun-runner Bradford Green. The crash slams the narrative into a hospital screen. Your energy bar is literally a heart-rate monitor: push the call button timely, sip water, sign release papers, or flat-line and reload. The sequence is short but potent, grounding the whole noir melodrama in bodily frailty. It also introduces the head-injection cameo payoff: during discharge, a nurse mentions “those digital head jobs over at City Hall,” sly product placement for Tsunami’s offer.

Station Routine & Squad Banter

Back at the precinct, locker-room talk doles out hints. Partner Doug Kindall, a doughnut-theorist in mirrored shades, drops Danny-Glover-grade lines (“I’m getting too old for traffic accidents, kid”) while the younger beat cop, Carla, quotes Terminator 2 as she triple-checks her Glock. This banter hides gameplay tips, Doug practically telegraphs the correct sequence for a domestic-violence call (“Radio first, approach left, watch those stairs”). Ignore the chatter and you flub a step, which slashes your score or, worse, trips a fatal cut-scene.

The Yacht Sting

The grand finale has you tail Green’s motor yacht, stakeout style. Using binoculars, you must capture three photos: crates marked “SCUBA GEAR” (sarcasm courtesy of pixel artists), Nico Dillon unloading assault rifles, and an overheard exchange referencing the 1984 double homicide. Snap everything, radio it in, and wait for the Coast Guard. Storm the boat prematurely? Dillon flash-bangs you, cueing a Game Over. Wait patiently, use the spotlight, hail over the megaphone, and the suspects surrender into a cut-scene where Jake finally sees his parents’ killer cuffed. Revenge is served chilled, like rationed coffee in the station commissary.

Failure Fest

Mishandle your service weapon after a shoot-out? Internal Affairs suspends you. Enter an evidence room without signing the logbook? The game ends with a text wall longer than a Miranda card. Walls merges Sierra’s love for instadeath with his own love for training-manual scolding, creating gameplay that thrives on paranoia. The only safe path is the right path, and the right path is whatever the California Penal Code scribbles in its margins.

Legacy and Influence

Commercially, Blue Force made smaller ripples than a pebble dropped in a water-cooler jug. Tsunami folded by 1996, their final newsletter promising “exciting interactive TV projects” moments before the lights went out. Yet the game’s ideas seeped sideways. Ken Allen’s dynamic MIDI score, scaling tension based on invisible “threat” variables, proved you didn’t need iMUSE to make adaptive music. Micro-titles like Outlaws (1997) and even SWAT 4 (2005) would refine that trick, but Blue Force planted the seed.

Walls’s draconian procedural flags echo loudly in Papers, Please, Not Tonight, and Return of the Obra Dinn, where bureaucratic mis-clicks yield cold consequences. Those games may look nothing like mid-’90s VGA police dramas, yet they worship the same altar: rule compliance as core tension. And the VHS-to-floppy injection? You can trace that urge for personal cameo all the way to modern sports-game face-scan suites. When EA’s servers misread your selfie today, thank, or blame, the dusty ancestor that asked you to envelope a Hi-8 tape in bubble wrap.

Preservationists keep Blue Force alive via ScummVM, though it still sits behind a “good (unsupported)” compatibility flag. The community’s biggest hurdle is the compressed voiceless disk space: without CD audio or actors, modern players misread its somber MIDI horns as comedic. Meanwhile, speed-running shuns the title because its unskippable patrol loops throttle any potential world record. But archivists appreciate its unfiltered snapshot of early ‘90s software morality: a time when designers believed video games could teach civilians that procedure saves lives.

As for the cameo service, collectors cite only two confirmed return disks in existence, both featuring different teen faces awkwardly grafted onto City-Hall tourists. One floppy surfaced on Reddit last year; the owner booted it under DOSBox, grabbed screenshots, then locked the disk in a fireproof safe. The other belongs to Jim Walls himself. During a 2014 Classic Gaming Expo panel, he produced the disk from his blazer pocket like a detective flashing a warrant. The applause that followed was half nostalgia, half disbelief that twenty-nine ’90s dollars could buy you permanent residence in a 256-color time capsule.

Closing Paragraph + Score

Replaying Blue Force in 2025 feels like rifling through an evidence locker sealed since Clinton’s first term, dusty, definitely dated, undeniably instructive. Jim Walls’s obsession with procedure turns mundane acts (parking, photocopying, labeling) into high-stakes button combos that predate modern indie bureaucracy simulators by decades. The plot tied to Jake Ryan’s orphan trauma slides into melodrama just shy of a primetime soap, yet those emotional beats anchor the checklist simulacrum in genuine stakes. And the “Get Injected” side hustle? It remains the single strangest de-luxe DLC ever sold via snail mail, a reminder that the ‘90s wanted to include you in the story long before cloud saves and face-tracking cursors made it easy. Blue Force isn’t the missing cornerstone of adventure-game history, but it’s a solid brick, one worth studying, especially if you’ve ever wondered what happens when a real highway patrolman sneaks a design document past marketing.

Final Score: 7.2 / 10.0, issued like a well-deserved citation: firm enough to sting, indulgent enough to tell over coffee. Will I replay it after ScummVM finally flips that compatibility switch to “perfect”? Rhetorical question. Self-answer: I’ve already queued the floppy in Drive A and set my VCR to SP mode, just in case Jim Walls asks for a sequel cameo.