Some videogames knock politely; Doom kicks the door off its hinges, stomps in with a shotgun the size of a Buick, and redecorates the foyer in EGA crimson. Is id Software’s 1993 opus bizarre or classical? (Both: picture a Bach fugue scored for chainsaw and MIDI bass.) Underrated or overrated? Ask the “it’s just Wolfenstein in space” crowd and they’ll say overrated; measure influence by the number of keyboards pounded flat in death-match rage and you’ll call it criminally underrated. Fundamental or forgettable? Imagine gaming history as a fossil record: Doom is the Chicxulub impact layer, everything before looks quaint, everything after wears its crater dust. And the absurd hook I’ll swing from for the next few thousand words? Those fluorescent-green explosive barrels. They sit there humming like radioactive piñatas.

Historical Context

Winter 1993: Clinton is still learning the Oval Office Wi-Fi password, Jurassic Park toys are devouring holiday allowances, and the local arcade’s Neo-Geo cab loops “Winners Don’t Use Drugs.” Meanwhile, in Mesquite, Texas, a seven-person team called id Software is sleeping under desks to finish a darker, faster successor to Wolfenstein 3D. Lead coder John Carmack has wrung pseudo-3-D corridors out of a 486 like juice from a rock; John Romero is trotting around blasting Pantera and promising level geometry that will “melt faces.”

Id’s résumé so far reads like a puberty diary: Commander Keen (Saturday-morning platforming), then Wolfenstein 3D (Nazis plus gibs), and now Doom, a metal-album cover rendered playable. No traditional publisher wanted a hyper-violent demon shooter, so id doubled down on shareware: Episode I free on every BBS and magazine disk, Episodes II and III sold direct for thirty-ish dollars. On 10 December 1993, business manager Jay Wilbur uploaded the shareware to a University of Wisconsin FTP server; the internet promptly collapsed in what sysadmins still call the “Doom flood.”

Contagion was immediate. Two weeks later my high-school Novell network hosted clandestine death-matches over lunch. By late 1995 analysts joked that Doom lived on more PCs than Windows 95, a statistic Microsoft never convincingly disproved. Retail boxes eventually hit shelves via GT Interactive in the 1995 Ultimate Doom reissue, but the real marketing department was word of mouth: if you owned a floppy drive and a modem, Doom found you.

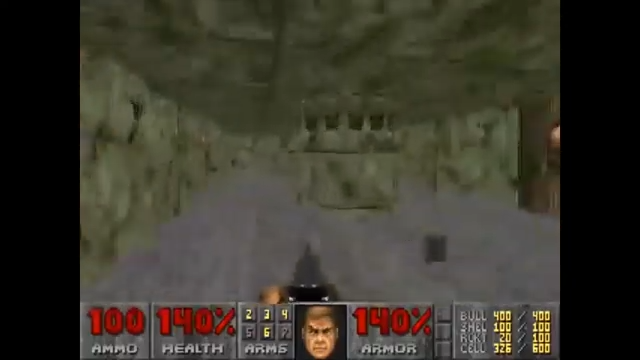

My first session unfolded on a classmate’s 486 DX2/66. Title screen: Doomguy knee-deep in demons. New Game. E1M1’s palm-mute riff detonated the room. Twenty seconds later a green barrel caught a stray pistol shot and vaporised three zombies in stereo screams. I thought, “Games will never need to look better than this.” (Reader, I was only half wrong; they still need to feel this good.)

Mechanics

Doom is pure locomotion, forward momentum weaponised. Walk speed verges on rollerblades, strafe-running turns corridors into NASCAR tracks, and the hit-scan shotgun reloads with a macho pump that makes your space marine grunt in approval. Mouse-look? Not yet. Jump button? Please. Carmack’s engine fakes verticality with clever projection; aiming up or down isn’t necessary when auto-aim hoovers buckshot into cacodemon face meat.

Levels fuse tech-base chic and satanic masonry, stitched together by colour-coded keycards, blue, yellow, red, that turn hallways into murderous Rubik’s Cubes. Doors hiss, lifts clunk, and secret walls slide back with a smug snnck, exposing rocket launchers, or, if the mapper felt cheeky, more barrels. Those barrels! They’re Chekhov’s gun in cylindrical form: see neon green, twitch trigger finger, ignite chain reaction, cackle.

Weapons ascend from pop-gun pistol to BFG 9000, a plasma watering can that erases rooms via invisible tracers and light-speed math. Shotgun for crowd control, chaingun for stun-locking sergeants, rocket launcher for tactical self-harm, plasma rifle for door-way spam, chainsaw for ammo savings, BFG for when halving the frame-rate feels worth it. The arsenal’s crunchy feedback remains a gold standard modern shooters still chase.

Enemies? Brown-shirt zombies, fireball imps, shrieking lost souls, corpulent cacodemons, arachnotron web-brains, and the Cyberdemon: a minotaur made of rockets and hubris. Each monster telegraphs attacks with distinct audio cues, Bobby Prince’s monster barks function like musical notation. Hear an imp gargle, pivot, fire. Spot a barrel beside a shotgunner, laugh maniacally, fire. It’s a rhythm game where the notes are shells and your score is corpses.

Multiplayer detonated expectations. Doom introduced deathmatch to our lexicon, letting up to four marines rip each other apart over IPX LAN or, with arcane dial-up software, the early internet. Cooperative mode existed too, but sessions inevitably devolved into “accidental” shotgun blasts followed by rocket-fueled apologies.

Modding blossomed because Carmack left assets unpacked. Within weeks fans were editing levels with TED 5 and BSP, birthing the .WAD underground. Want a Simpsons overhaul or a Teletubbies reskin? Someone’s made it. That open-door policy arguably fathered the modern mod scene, from Counter-Strike to Garry’s Mod.

Quick mini-rant on HUD design: Doomguy’s brow-wiggling mug is still gaming’s best health bar. He grimaces at 60 HP, bleeds at 30, and sports a power-up grin when juiced. Modern minimalist UIs feel sterile by comparison. And praise the automap: a glowing wire-frame spiderweb somehow more legible than half today’s AAA mini-maps.

Legacy and Influence

First-person shooters divide neatly into pre- and post-Doom. The shareware model rewired distribution; mod support seeded careers (hello, Valve); network code made LAN cafés viable businesses. Technically, Carmack’s engine popularised binary-space partitioning, underpinning later engines from Build to Source. Design-wise, the movement-gunplay loop powers modern hits like DUSK and Ultrakill; even Fortnite’s shotguns echo Doom’s spread pattern.

Culturally, Doom courted controversy like a rock star courts hotel fees. Senators waved screenshots during 1994’s violence hearings; evangelists dubbed it a “pathway to Satan.” After Columbine, trench-coat mods became scapegoats. Yet the game endured, partly because its gore is comic-book exuberant, red pixels spurt, vanish, done.

How pervasive? By 1997 Doom ran on calculators, oscilloscopes, even an ATM. In 2023 modders ported it to a Roomba; the robot spun circles while blasting E1M1 through tinny speakers. Somewhere John Romero smiled.

Yet few successors replicate Doom’s kinetic purity. Modern shooters drown in reload animations and XP bars; Doom asks only, “Is that thing alive? Remedy that.” Its absurd green barrels remain didactic: keep moving, keep shooting, and never underestimate explosive furniture.

Closing Paragraph + Score

Thirty-plus years on, I still measure FPS bliss in barrel units. Does a new game coax the same giddy calculus, “One stray shot and the room goes nuclear”? Rarely. Boot Doom, tap “IDDQD” (old habits die hard), and the feedback loop hits like fresh-opened tab cola. Bizarre and classical, simultaneously overrated by marketers and underrated by anyone who hasn’t felt a Cyberdemon rocket shake a Sound Blaster, Doom is unassailably fundamental. Final verdict: 10 / 10, because some classics aren’t just good; they’re the reason the word classic exists at all, humming like a green barrel eager to explode.