Is Gateway 2: Homeworld the brilliant sci-fi banquet everyone forgot to RSVP to, or the crusty Tupperware lingering in interactive fiction’s communal fridge (complete with a passive-aggressive sticky note: “DO NOT microwave, Heechee radiation hazard!”)? Does it deserve an honored seat at the high table of early-’90 s adventure design, or is it wobbling atop an IKEA footstool marked obscure curio, handle with fond nostalgia only? Short answer, yes, to all of the above. Long answer, strap in, because this sequel to Legend Entertainment’s Gateway (1992) is at once wildly ambitious and stubbornly classical: pure parser at heart yet grafted onto VGA illustrations, General MIDI crescendos, and so many UI toggles that you half expect Clippy to pop up asking, “Searching for a verb?” Underrated or overrated? Depends on whether your wrist still remembers typing DISENGAGE RETRACTOR ARM at 2 a.m. Fundamental or forgettable? I’d call it crucial precisely because it refuses to behave like a polite ’90 s point-and-click; it’s the cantankerous older cousin who brings graph paper to a console party and proceeds to win everyone over by making the beer disappear (Heechee transporter joke fully intended).

Historical Context

To understand why Gateway 2 matters, picture the PC-adventure scene in 1993. Myst is quietly brewing its CD-ROM cage match for that holiday season; LucasArts is planting rubber chickens with prosaic pulleys on them (Day of the Tentacle); Sierra has long since taught us to save early, save often, then watch our avatar drown in a puddle of pixelated sludge. Legend Entertainment, helmed by Bob Bates and Mike Verdu, decides to buck that talky point-and-click wave by doubling down on parser-driven design, albeit with slick VGA stills and a mouse-selectable verb palette for newcomers whose fingers quiver at the thought of INVENTORY.

The original Gateway, adapted from Frederik Pohl’s Nebula-snatching novels, sold just well enough to green-light a sequel. Inside Legend’s 1993 batting order the plan looked like this: close out the parser era with Gateway 2, then pivot to pure mouse control in Companions of Xanth the following year. If the studio’s catalogue were a band discography, Gateway 2 is the sprawling prog-rock finale before the label forces everyone into radio-friendly choruses.

I spotted the game in a Rhode Island Babbage’s, the storefront humming with 486 demo stations all dutifully looping Wing Commander II. A lonely big-box copy of Gateway 2 sat beneath a shaky fluorescent tube, its cover promising shimmering alien spirals and quoting a Pohl blurb I’d never seen. I bought it for the included novella, teenagers are weird like that, and wound up glued to my DX2-66, timing disk-swap prompts between episodes of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (Quark would’ve loved the Heechee artifact trade; latinum practically drips from every puzzle).

Meanwhile the rest of the industry was sprinting toward multimedia: talkies, FMV, pre-rendered sprites wearing their pixel lighting like Elizabethan ruffs. Legend’s decision to ship an unabashedly text-heavy game in 1993 felt contrarian, maybe even foolhardy, yet also defiantly romantic, an admission that the parser, if handled with care, could still out-think a gigabyte of grainy QuickTime. They even resisted the lure of voice acting, believing that a deft line of prose inside the player’s head sounded better than any Sound Blaster channel could manage. That restraint gifts Gateway 2 a timelessness its FMV contemporaries lack; blocky actors age poorly, but text rendered in VGA Chiclet fonts remains forever 640 × 480 sharp.

Legend also leaned hard on the license. Pohl’s Gateway novels were already retro-future classics, exploring humanity’s complicated tango with a vanished alien race called the Heechee. Instead of slapping a brand decal onto a generic quest, the designers wove canonical plot strands directly into gameplay. Licensed games of the era usually settled for less, Batman sprites pasted on recycled platform engines, anyone?, so Gateway 2’s literate fidelity felt downright luxurious.

Mechanics

Let’s cut to the Heechee chase, yes, the game literally starts with one. Moments after boot-up you’re sprinting down Gateway Station’s metal corridors, alarms strobing crimson as a saboteur’s bombs tick toward plasma confetti. The parser hums beneath VGA stills: RUN DOWN CORRIDOR, DIVE INTO ESCAPE POD, CLOSE HATCH. Nanoseconds later you’re free-falling toward the lunar surface, sound-tracked by a MIDI bass line doing its best John Williams impression. It’s the adventure-game equivalent of a cold-open cliff-hanger, action first, exposition later, and it works.

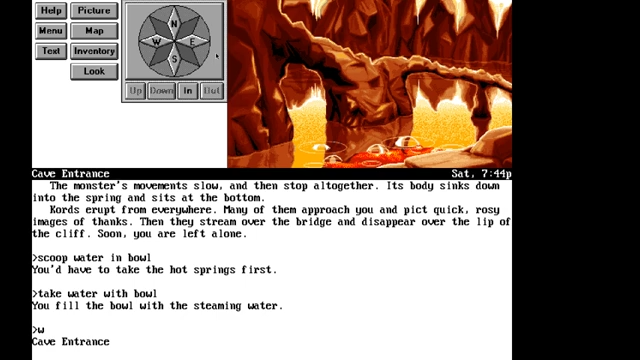

Unlike contemporaries that funnel every command through Swiss-army verbs like USE, Legend’s hybrid interface offers three input vectors. Purists type free-form commands (“>HACK CONSOLE”). Mouse dabblers click a verb–object palette arrayed beneath the illustrations, think proto-SCUMM bar. Diplomatic players (my tribe) swap fluidly, typing for precision but clicking when their wrists need a breather. Conversations swap you to a menu of topical questions; pick one, and the NPC responds, no guess-the-noun agony, no parser gaslighting, just contextual prompts that feel almost BioWare a decade early. Synonyms abound, the game politely groks TURN ON, ACTIVATE, even the 1337-adjacent INIT, so the dreaded I don’t understand that verb appears only when you genuinely deserve a slap on the knuckles.

Structurally the journey unfurls like a four-act novel. Act I: Gateway-Station sabotage. Act II: exploratory jaunts in a Heechee scout craft, each hop keyed to mysterious coordinate codes. Act III: infiltration of “the Artifact,” a cylindrical megastructure parked in the Kuiper Belt so colossal it makes Rama look like an exhaust pipe. Act IV: the titular Homeworld, tucked inside a relativistic bubble where centuries dilate to minutes and ancient fears still rattle the furniture. The overarching route is linear, Legend wanted its story served hot, but side excursions let you detour, loot, and learn at leisure.

Snapshot time: early in Act II you strap into that Heechee scout. The cockpit’s UI appears as a bespoke mini-game, a grid of glyph-etched sliders whose sine-wave readouts scream engineering final exam. Misalign an inertial damper and the ship vibrates like a phone stuck in developer-mode rumble, then pinwheels into vacuum. Nail the waveform alignment and hyperspace smears the screen white, leaving you exhilarated, a tiny text hero punching far above a 3.5-inch diskette’s weight.

Puzzle design alternates between classic lock-and-key (locate the crystalline pass card, open the stasis vault) and breathtaking high-concept challenges. Mid-game you face a Heechee genetic synthesizer: six enzyme vials, a spool of segmented DNA, a centrifuge that hums like a ’70 s blender. Your goal? Splice a microbe capable of digesting toxic slime clogging an air duct. Too aggressive and your creation escapes, corroding your EVA suit three turns later. Too mild and it just sits there gurgling. The optimal genome lies in the Goldilocks zone, equal parts science, intuition, and notebook scribbles that look suspiciously like high-school bio homework gone rogue.

And here’s the absurd motif I kept tugging: the omnipresent Compass Rose that dominates the screen’s upper-left quadrant. Eight cardinal prongs shimmer in slate-gray, offering IN, OUT, UP, and DOWN buttons around their rim. Whether you’re sneaking through ventilation shafts or lecturing Heechee academics, that spoked wheel never leaves your side, a cosmic fidget spinner whose highlights shift whenever an exit is legal. I started anthropomorphizing it: North-Fred, East-Erin, South-Sal, West-Wendy, plus the vertical twins Up-Ulysses and Down-Delilah. Every time the story cranked up the tension, I found my eyes darting to Fred and Erin for reassurance. Who needs a mini-map when you’ve got a steel-gray snowflake whispering “You are here… for now”?

Nitpicks? Plenty, delivered with affectionate rant. The VGA palette leans hard on salmon nebulae; by Act III I’d have sacrificed a radiation badge for one brooding shade of villainous purple. The MIDI score occasionally slips into elevator lounge when menace would serve better (I suspect the composer’s MT-32 demo disc got stuck on “Soft Rock Jam 03”). And yes, you can still kill yourself by typing EXIT AIRLOCK without a suit, Legend preserved a dash of Sierra’s Darwin-award philosophy because, hey, space is unforgiving, kids. Crucially, there’s no behind-the-scenes autosave to bail you out. Manual saving (and its twin sibling, manual loading) remains the player’s lifeline, just as the parser gods decreed.

Legacy and Influence

Why isn’t Gateway 2 whispered about alongside Grim Fandango or Monkey Island? Timing. By late 1993 CD-ROM talkies dominated magazine covers; anything parser-based looked like grand-dad’s slide projector. Legend itself pivoted immediately, Companions of Xanth ditched typed commands the following year, and mainstream press treated that shift as evolutionary inevitability. Gateway 2 thus became the last major commercial parser adventure published in North America, a bittersweet milestone akin to the final vinyl pressing before the industry’s CD rush.

Still, its influence lingers. Mike Verdu, co-designer, later steered narrative frameworks on Command & Conquer 3 and Dragon Age II, carrying forward the lesson that dialogue choices work best when their emotional valence is crystal-clear, an idea first rehearsed in Gateway 2’s click-to-ask conversation lists. Glen Dahlgren mined similar clarity when he helmed Death Gate (1994), giving us dragon librarians whose sardonic quips feel like Heechee AI cousins.

Within modern interactive fiction, Gateway 2 is frequently cited as proof you can blend robust parsers with lavish illustration without sacrificing agency. Glulx epics, Emily Short’s Counterfeit Monkey, Andrew Plotkin’s Hadean Lands, inherit its spirit of crunchy simulation layered beneath painterly panels. Even Twine authors borrow the trick of embedding fiddly mini-games inside prose, echoing those coordinate sliders in the Heechee cockpit. Each time a player drags a digital slider in a web-IF piece, a faint ripple crosses the Kuiper Belt where Gateway 2’s Artifact still drifts.

Why did the game stay niche? Partly the homework factor: you really do keep a paper notebook, jotting numbers in base-12, sketching star maps, and annotating that indispensable Heechee pass card like a caffeinated librarian. For a 1993 teenager trapped between dial-up screeches, that was nirvana; for casual CD-ROM dabblers expecting full-voice exposition, not so much. Marketing didn’t help either: static VGA corridors couldn’t compete with Rebel Assault’s FMV dogfights blinking seductively in store windows.

Yet the finale, meeting the reclusive Heechee on their time-dilated sanctuary world and confronting the cosmic horror they fled, lands a thematic sucker punch. It asks players to weigh self-preservation against galactic stewardship long before Shepard agonized over Reaper casualties. IF scholars now place Gateway 2 beside Planescape: Torment in the “existential dread made personal” category. Both revolve around ancient civilizations ducking inevitable doom, both hinge on provocative choices about identity and moral responsibility, and both hurl lore dumps heavy enough to bend your mental gravity.

Closing Paragraph + Score

Booting up Gateway 2: Homeworld in 2025 feels like unearthing a perfectly preserved Atari joystick, except the stick now unlocks star-gates, lets you toggle a compass rose as comforting as a cosmic snowflake, and reminds you that one misplaced keystroke can still vent your organs into vacuum. Messy in spots (salmon nebulae, we meet again) and occasionally brutal (never open a Heechee airlock without reading the fine print), the game’s narrative ambition and systemic ingenuity remain startlingly fresh. Text adventures may have ceded mainstream ground to polygon juggernauts, but Gateway 2 proves the parser still punches above its weight when wielded with imagination and a sprinkle of cosmic dread. Final verdict? 8.3 / 10, a minor classic that slipped through the mass-market wormhole yet continues to ripple across the sub-space of interactive fiction, one carefully typed verb at a time.