Is Global Domination the weird uncle of early-1990s strategy games, or just a misunderstood cousin that shows up to the family reunion in a garish Risk-cosplay cape and insists the hors d’oeuvres be color-coded “brown” and “purple”? (Rhetorical question; self-owning answer: yes, to both.) Released in 1993 by Impressions Games, right after they taught us to pave Roman roads in Caesar and just before they’d let us starve medieval peasants in Lords of the Realm, this DOS/Amiga curio straddles the line between bizarro cult classic and clunky also-ran. Underappreciated? Definitely. Overhyped? Only if you were the kid who thought VGA stood for “Very Good Audio.” Fundamental? Maybe not in the grand-strategy pantheon, but try telling that to my sleep-deprived teenage self who feared the midnight rebellion of those treacherous purple provinces (fun fact: they revolt if you spread forces too thin). In other words, Global Domination is the kind of game that asks, “What if Risk grew opposable thumbs and a snarky sense of geopolitics?”, then answers, “Here’s a clunky real-time mini-battle, don’t trip over the interface.”

Historical Context

Impressions’ 1992-94 run now looks like a developer speed-running its own evolution tree. Caesar (1992) had just taught us that aqueducts are sexier than laser pistols, if laid out on a perfect isometric grid, anyway. That success emboldened founder David Lester and designer Simon Bradbury to push beyond city builders and into globetrotting conquest, green-lighting Global Domination in a moment when the PC market was caught between VGA bravado and the Windows 3.1 “multimedia revolution” (read: a thousand sound-card drivers screaming into the void).

Board-game conversions were trending, Civilization had already proven that hexes could print money, while Chris Crawford’s Balance of Power still loomed large as the thinking person’s nukefest, but few studios dared wrap Risk’s beer-and-pretzels appeal in layer after layer of number-crunching. Impressions dove in head-first: 180+ territories (instead of Risk’s humble forty-two), four historical scenarios (1914, 1939, 1995, and the gloriously bonkers asteroid-afterparty of 2500), and a hotseat multiplayer mode guaranteed to turn your best friend into a sofa-sleeping enemy.

I remember spotting the big yellow box at my local Software Etc., nestled between Wing Commander III’s space-opera glamour and WordPerfect’s teal apocalypse. The back-of-box bullet points promised “intelligence operations” and “unit obsolescence,” which sounded impossibly grown-up to a 14-year-old more accustomed to counting quarters at the arcade. (Could a spy satellite be as thrilling as topping the NBA Jam high-score board? Spoiler: if the satellite sabotaged Queen Victoria, sorta.)

For Impressions, Global Domination filled an experimental gap: something weightier than Caesar yet less historically anchored than the feudal spreadsheet soon to become Lords of the Realm (1994). It was a pivot title, part proof-of-concept, part head-rush, and, in hindsight, the missing link explaining how the studio later nailed the genre fusion in Lords II and Pharaoh.

Mechanics

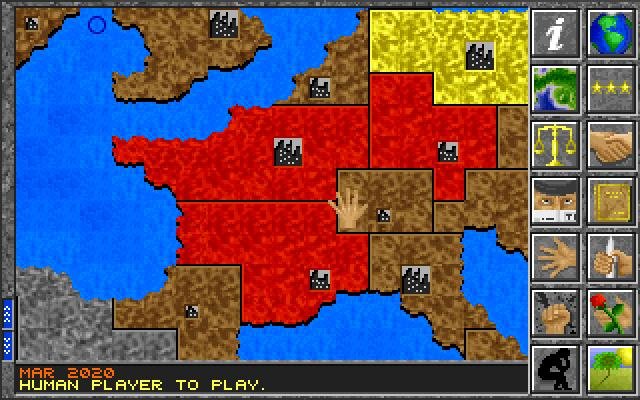

Boot the game and you’re greeted by that wonderfully chunky globe texture, imagine Mode 7 having a midlife crisis, and a MIDI soundtrack cheerfully insisting global conquest is jaunty, not genocidal. Setup starts with the random territory draft: one second you own Iceland, the next you’re babysitting both Congos and wondering whether your empire is a Jackson-Pollock gag. Income flows from territory value, rich Europe bankrolls tanks, while poor Sahara merely provides awkward conversation. New players promptly overextend, cueing the game’s signature absurdity: “purple territories,” i.e., revolting provinces that flash violet like geopolitical eczema. The purple-plague becomes your paranoid leitmotif; every move thereafter is a frantic hunt for garrison ratios (“Is three infantry enough to keep Siberia calm? Trick question: Siberia never stays calm.”).

Combat offers two flavors: quick resolve (Risk-style dice behind the curtain) or the infamous tactical mini-game. Choose the latter and you drop into a 2-D battlefield where units, infantry, armor, ships, bombers, trundle across a scrolling map that looks like someone smudged Sensible Soccer with mud. Critics in 1994 called it “clunky” and “not up to current standards,” which is charitable shorthand for “scroll-lag city.” Yet, and here’s the twist, the jank breeds charm: watching my pixelated dreadnought overshoot Newfoundland and beach itself on virtual Labrador has aged into a meme-worthy delight. (Rhetorical question: did I manually drive a digital boat onto an ice floe? Self-answer: yes, captain, and I’d do it again.)

Unit obsolescence sneaks in as a low-key genius system. Clinging to World War I biplanes in the 1995 scenario feels like showing up at an e-sports tournament with a ball mouse, eventually the game politely declares your airborne antiques “historical artifacts” and refuses to let them launch. Likewise, research trees drip-feed upgrades, which means you can’t just spam tanks; you need air cover, naval projection, and, deliciously, covert intel. Funding espionage yields spy icons that let you peek at an enemy’s territory value or foment rebellion (extra purple!). It’s the same dopamine hit Civilization players get from stealing tech, but with the added schadenfreude of watching Napoleon Bonaparte lose Quebec to insurgents he’s never met.

Speaking of Bonaparte, the AI roster is like a time-traveling dinner party curated by a trivia host who spiked the punch. General Custer resists cavalry obsolescence (of course he does); Queen Victoria bankrolls navies like she’s back on the high seas; Napoleon aggresses until he runs out of baguettes or neighbors. Their personalities are simplistic by 2025 neural-net standards, but in 1993 they felt alive enough to warrant grudges. I still blame Bismarck for teaching me what blitzkrieg actually means.

Multiplayer, hotseat only, turns living rooms into diplomatic mosh pits. Nothing frays sibling bonds faster than betraying the temporary truce to “just secure Scandinavia, honest.” (The manual suggested using poker chips as off-board troop markers; my group upgraded to M&M’s, which inevitably devolved the post-game map into a sticky biohazard.)

And then there’s the UI quirk where every action confirmation beeps like a life-support monitor. Under pressure those beeps syncopate into a rhythmic mantra: Do, not, overex, tend, (spoiler: you will). Combine that with the day-glow palette of unit sprites, and the entire aesthetic lands somewhere between military-history zine and early Nickelodeon bumper.

Legacy and Influence

So did Global Domination change the world, or merely paint parts of it purple? Commercially it never cracked bestseller lists; Caesar outsold it, and Lords of the Realm would soon overshadow it in both critical buzz and Windows 95 shelf-space. Yet bits of its DNA are oddly persistent. The concept of world-scale Risk plus tactical micro-battles pops up later in Total War (replace beepy sprites with lavish 3-D), and the colored-territory revolt mechanic is the spiritual godparent of Civilization V’s city-state unrest meter.

Impressions themselves recycled lessons: the “auto/real-time toggle” became a tent-pole of Lords I’s castle sieges, while tech-edge obsolescence drifted into Pharaoh’s luxury-goods economy (swap obsolete biplanes for fad-expired papyrus). Perhaps more telling is what Global Domination tried and abandoned. No subsequent Impressions title attempted a four-era campaign spanning from Great War trenches to speculative asteroid wastelands; the studio pivoted toward tighter historical focus, suggesting GD’s kitchen-sink ambition was both inspirational and cautionary tale.

Among the cognoscenti it retains cult-status for two reasons. First, the AI-leader gimmick predicted the “named persona” fad we’d later see in Civilization IV’s aggressive Montezuma memes. Second, and here’s the absurd thread, it’s still the only commercial strategy game where the color purple induces a PTSD-style twitch. Streamers revisiting GD on abandonware nights delight viewers by deliberately triggering purple uprisings, a clip-bait ritual akin to summoning the ghost truck in Grand Theft Auto V.

Chuck Moss’ Computer Gaming World review called the game “a failure and a surprising success” in one breath, proclaiming it “addictive” despite its “clunky” battlefield. That verdict aged gracefully: modern players forgive the rough edges because the macro-layer still nails that “one more turn at 2 a.m.” syndrome. Meanwhile, modders strip out the tactile battles entirely, turning GD into the sleek Risk-on-steroids tablet game it always wanted to be, proof that the strategic skeleton was solid all along.

Yet why didn’t the big studios riff on the purple-plague? My pet theory: players hate losing territory to RNG rebellion after they’ve “won” a war. It’s the same reason few RTS games adopt SimCity-style crime meters, nobody wants their conquering Panzer corps then to babysit a populace demanding healthcare. Global Domination forced you to, and in doing so scared off mainstream adoption.

Closing Paragraph + Score

Like a beloved B-movie found on a dusty VHS, complete with tracking-line jitters and an end-credit ballad that really should have won a Grammy (fight me), Global Domination is equal parts awkward and unforgettable. I can’t promise you’ll love the tactile battles, nor that the UI won’t beep its way into your nightmares, but I dare you not to cackle the first time a smug AI Napoleon watches half his empire go violently ultraviolet. Fundamental? No. Tragically neglected? Absolutely. Sometimes the road to genre greatness runs through a purple-stained detour, and this game is the neon sign pointing the way. Final verdict: 7.2 / 10, dock points for clunk and creak, add bonus XP for every time the purple revolt makes you swear allegiance to garrison spreadsheets. Roll the dice, commander; the world (and its color palette) awaits.